Christian Petzold’s Yella (2007) and The Dardenne Brothers, Two Days, One Night (2004) both engage in a conversation around how Neoliberalism functions in a manner which places precarious individuals in an ungrounded state, purposefully leaving one both emotionally, and physically dependant on greater governmental power. With the rise of technology, all form of pre-existing boundaries dissolve, creating timeless and spaceless working conditions. The main protagonists in both Yella and Two Days, One Night negotiate the transversal nature of the borders of time, their personal relationships, and the boundaries between “private” and “public” spheres. This is demonstrated through the erasure of the borders between work and rest, as they once existed prior to Neoliberalism’s promotion of unending growth and economic production. These two films stand as a testament to how Neoliberalism creates a “borderless existence” as work and labor are no longer easily separable, the notion of “public space” becoming extinct. The continuous movement of both Yella and Sandra enact as a metaphor for their difficulties with their subjectivity; as they travel from site to site, they cross not only geographical boundaries but also the boundaries that separate and paradoxically connect individuals in precarious living situations.

In Tertiary Time: The Precariat’s Dilemma, Guy Standing discusses how a human’s ‘basic asset’ is time; as beings, one embodies time. Consequently, it becomes exploited as it is the most precious aspect of life and must be carefully negotiated, it being something which flows through all beings makes it the first thing targeted under capitalism.[1]Typically, one is compensated for their time to benefit from “free time”, however as a precariat time no longer can be defined by these borders of being “on” and “off” duty, as it was historically separated as the Vita Contemplativa (the ancient Greek term referring to the free, pleasurable life) and Vita Activa (referring to the labour required to enjoy the Vita Contemplativa).[2] Through continuously being faced with the possibility of making more money (or suddenly having none) one is forced to sit in an in-between place where financial stability is never a certainty.

Tied to a loose rope of possible financial gain, both Yella and Sandra are forced to exist with no “off time”, they must continuously use their emotional labor to secure the basic cost of existence. These films visualize this dilemma as their continuous physical displacement is reflective of their inner emotional turbulence.

Yella’s subjectivity is transformable as the viewer is unsure of her corporeal existence. One observes her interactions with others yet remains uncertain where she would exist on a linear timeline. In this manner, she complicates our understanding of “clock time.” She is given various meeting times and places by her business partner, Philipp, which enact as “time stamps” for the viewer in a cinematic universe which seems to exist outside of “real-time.” Petzold’s film feels reminiscent of a tableau, an artificial simulation of a place grounded in the viewer’s reality, which becomes estranged through a lack of what the viewer is expecting to witness. A tableau, typically understood as a ‘still view of life’ or a ‘stage setting’ leads to the seeming timelessness in Yella. It furthers the Neoliberal dilemma of existing in a zero-hour work week and the seeming inexistence of bordered time. In contrast, the boundaries of time are much more literal in their interpretation in Two Days, One Night filmed in the ‘Cinéma verité’ style, “truthful” to its real-time capture. Even though this film is set in a fictional universe, the adaptation of the observational documentary format blurs the boundary between reality and fiction. This creates a precarious boundary between the real living experience of many and the dramatic, nearly thriller effect of Two Days, One Night.

French Anthropologist Mark Augé discusses how the place where one is born is also the placing of identity onto a person. The geographical boundaries which surround one not only function to contain large groups of people but also to hold them accountable to a range of biases which root from place.[3] “Non-places”, coined by Augé, are locations which do not hold the subjectivity of its visitors, but rather act as ‘transition zones’.[4] Largely devoid of other beings, Yella and Philipp inhabit locations which lack any sense of humanity, furthering the image of how the urban space inhabited by humans becomes increasingly commodified and inhumane. In Two Days, One Night the camera is shaky, and always at eye level, creating the effect that as the viewer, one is always intertwined in the conflicts Sandra faces with her coworkers. The framing provided in Yella, is imbued with a sense of disconnection. Petzold is attempting to create a divide between the borders of real life, and the spectral life of Yella, this is done effectively using an extremely stable camera. One feels as though they are floating through the film’s universe, as if a ghost oneself, untouched able to the actions on screen.

Yella withholds a sense of uncanniness, in the Freudian sense of the unheimlich, (the unhomely) she herself becomes a borderless being which lacks any solid place of home. She remains continuously tethered to places which mark transition, or “non-places”. Sandra also inhabits a spectre like presence, like Yella she is placed in this in-between place where all the things which tie her to her to a stable, or improved future come loose. These films show by example, just how much one’s subjectivity is reliant on one’s economic status. A ghost is a perfect metaphor for the experience on Neoliberalism. The impossibility of rest, and an entity which permeates the physical boundaries of all spaces. Both directors highlight human nearness to death and mental health, an example of precarity on its own.

In The Human Condition, Hannah Arendt states that the term “public” signifies “two closely interrelated but not altogether identical phenomena: It means, first, that everything that appears in public can be seen and heard by everybody and has the widest possible publicity. For us, appearance—something that is being seen and heard by others as well as by ourselves—constitutes reality.”(Arendt.55)[5] Arendt argues that what makes humans “common” is their subjectivity, and their recognition of the other in the “outer world”. However, under Neoliberalism, where all land has become commodified, there is no more public realm where one can simply “be common”, prejudices around social class control how one can exist around others. Yella remains “homeless”, while in two days one night, Sandra’s home, her bedroom, functions as a form of retreat, a place to hide from the world which Yella does not hold privy to. Sandra uses the act of retreating or exiting the “public sphere” to simultaneously retreat from the anxieties around her dependance on her co-workers, and her families dependance on herself. Yella, whom also is attempting to gain independence, and support her father is similarly continuously coxed away from her privacy – and has no real home of her own – lacking the chance to ever reach true rest.

Lorey argues “Shared precariousness is thus a condition that both exposes us to others and makes us dependent on them. This social interdependence can express itself both as concern or care and as violence.” (Lorey.20). [6] Both films demonstrate how the community of the precarious face struggles in balancing their interdependence with their attempts to prioritize their own livelihood due to the separation of assets promoted through Neoliberalism. Lorey describes this as a “shared differentness,” the paradox that the thing which binds humans together, being the precarity of their being, is also what holds them apart.[7] In both films, this leads to various forms of aggression faced by Sandra and Yella, as they are both placed in the position of having to navigate multiple power relations to gain a state of security. Within the nuclear home, Sandra must also navigate social boundaries within her intimate relationships as a mother and wife. She is given the role of both financial as well as emotional support structure and does not allow her children to bear witness to her suffering under precarious work conditions. This is witnessed by the barrier she builds between how she presents within the escape of her bedroom vs in front of her children in the kitchen and dining area, where she attempts to bear the status of a “rational,” stable being. As the subjectivity of “worker” is so engrained within each individual, one is programmed to fight or compete to sustain this title continuously, leading to the creation of the Homo-Economicus. It also leads to the suppression of emotional responses in both Sandra and Yella.

In A Genealogy of Homo-Economicus, Jason Read argues that “It is possible to say that with real subsumption capital has no outside there is no relationship that cannot be transformed into a commodity, but at the same time capital is nothing but outside,”(Read.17).[8] This demonstrates the non-existence of boundaries under Neoliberalism, as an all-consuming force which marks each human as their own means of capital, the perfect Homo-Economicus has no relationship untouched by Neoliberal ideology. It leads to competition within the workplace and between individual relationships, eradicating Marx’s notion of “free time,” as now every waking moment is consumed by the commodification of the laboring body. Once the notion of outside, and inside becomes wholly eradicated, so does the notion of “public space”.

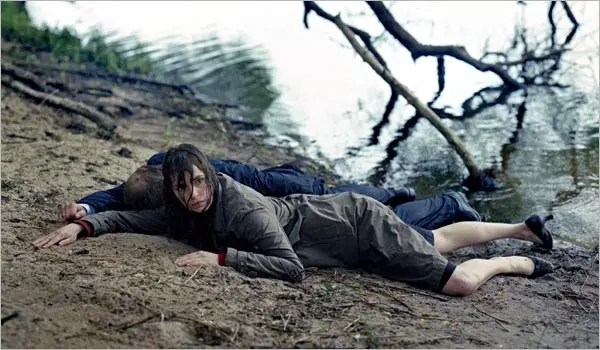

In both Yella, and Two Days, One Night, one bears witness to turbulence in Yella and Sandra’s subjectivity; they both seem to struggle to come to terms with how they are perceived outside of their title as workers. Yella, being a spectre of her former self, losing her life at the hands of her ex-husband in one of the first situations where she is placed in the passenger seat of her partner’s desires. He interpolates her as his competitor and refuses to witness a reality when she “beats” him in the economic competition. Under Althusser’s theory of interpellation, one’s identity is placed upon oneself at birth through greater governance structures. Embedded within oneself, it is what leads to self-governance and the reverence of drastic action to fulfill one’s identity.[9]

Neoliberalism transformed the gender hierarchy, where women who have historically been tied to the domestic sphere, providing “hidden labour” become inversed. Both directors made a poignant decision to cast female leads in portraying a picture of precarity. As they transition from site to site, they are always placed in the passenger seat of the car, and their male counterparts act as their travel companion. Unlike Yella, which seems to be an elusive place outside of reality, the filming of Two Days, One Night embeds the viewer directly within Sandra’s workplace conflicts. Both films highlight the dichotomy between the inexistence of any truly “private” property untouched by Neoliberalism and the complete lack of “public” space, as all urban space is carefully controlled. Sandra and Yella continuously navigated this paradox of experiencing both a lack of privacy and all “public” space being privately owned. Both in the context of their own private lives and the private lives of others.

Christian Petzold’s Yella (2007), and The Dardenne Brothers, Two Days, One Night (2004) take on wildly different stylistic formats to comment on how the rise of Neoliberalism has radically altered individual’s relationships to labor, causing an ungrounded existence, where the borders between free, and working time, physical, vs. emotional labor, private vs. public space, intimate vs. workplace relationships, become nonexistent. Both directors highlight their female protagonists restless state, contemplating the precarity of not only their financial survival, but also their own mortality. This is done to portray the urgency of how humans’ psychological well-being is manipulated through capitalism, but also to demonstrate the impossibility of removing one’s identity, from the subjectivity of worker, and self-governmentality under Neoliberalism. As the line between the Vita Activa, and Vita Contemplativa, becomes erased so does the ability to discern one’s subjectivity outside of one’s economic status. Sandra and Yella both inhabit ghostly existences; lost in the translation of the varying identities they must perform in order to navigate Neoliberal boundaries.

[1] Guy Standing, Tertiary time: The Precariat’s Dilemma “The Precaritatization of Time” Duke University Press 2013. pp.8

[2] Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition “The Term Vita Activa” University of Chicago Press, 1958. Pp.14.

[3]Marc, Augé Non-Places: An Introduction to Supermodernity “Anthropological Place” Translated by John Howe. Second edition. London: Verso, 2023, pp. 53.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition “The Public Realm: The Common” University of Chicago Press, 1958. Pp.52.

[6] Isabell, Lorey, State of Insecurity: Government of the Precarious. “Precariousness and Precarity”. Translated by Aileen Derieg. Brooklyn, NY: Verso, 2015, pp.20.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Jason Read, A Genealogy of Homo-Economicus: Neoliberalism and the Production of Subjectivity Koninklijke Brill NV, leiden, 2022. Pp.17.

[9] Louis Althusser On Ideology Trans. Ben Brewster. Verso Books. 2020. p.11